Researchers publish findings on GM mosquitoes

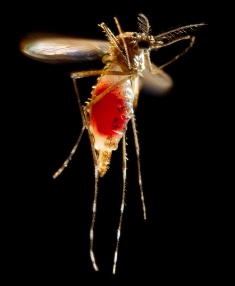

(NYTimes): Researchers have reported initial signs of success from the first release into the environment of mosquitoes engineered to pass a lethal gene to their offspring, killing them before they reach adulthood. The results, and other work elsewhere, could herald an age in which genetically modified insects will be used to help control agricultural pests and insect-borne diseases like dengue fever and malaria. But the research is arousing concern about possible unintended effects on public health and the environment, because once genetically modified insects are released, they cannot be recalled.

(NYTimes): Researchers have reported initial signs of success from the first release into the environment of mosquitoes engineered to pass a lethal gene to their offspring, killing them before they reach adulthood. The results, and other work elsewhere, could herald an age in which genetically modified insects will be used to help control agricultural pests and insect-borne diseases like dengue fever and malaria. But the research is arousing concern about possible unintended effects on public health and the environment, because once genetically modified insects are released, they cannot be recalled.

Authorities in the Florida Keys, which in 2009 experienced its first cases of dengue fever in decades, hope to conduct an open-air test of the modified mosquitoes as early as December, pending approval from the Agriculture Department.

Supporters of the research worry it could provoke a public reaction similar to the one that has limited the acceptance of genetically modified crops. In particular, critics say that Oxitec, the British biotechnology company that developed the dengue-fighting mosquito, has rushed into field testing without sufficient review and public consultation, sometimes in countries with weak regulations.

“Even if the harms don’t materialize, this will undermine the credibility and legitimacy of the research enterprise,” said Lawrence O. Gostin, professor of international health law at Georgetown University.

The first release, which was discussed in a scientific paper published online on Sunday by the journal Nature Biotechnology, took place in the Cayman Islands in the Caribbean in 2009 and caught the international scientific community by surprise. Oxitec has subsequently released the modified mosquitoes in Malaysia and Brazil.

Luke Alphey, the chief scientist at Oxitec, said the company had left the review and community outreach to authorities in the host countries. “They know much better how to communicate with people in those communities than we do coming in from the U.K.” he said.

Category: Science and Nature

The idea was well motivated in principle, and was seen as part of the fight against Dengue fever . Releasing sterile mosquitoes dilutes out those that can produce viable offspring. According to a full article by Bijal Trivedi in the current November Scientific American, it has been tried with irradiated insects , but this appeared to be first ever try outdoors of this kind with millions of mosquitoes released. She states that this was initiated by the biotechnology company Oxytec , and that there was prior announcement in a five minute spot on a Cayman nightly news broadcast plus a pamphlet that described the mosquitoes as sterile, “avoiding an mention of genetic manipulation”. In fact the new born females are genetically engineered to die by producing a toxin that impairs their muscle function.

She also states that an experiment is to be performed on Grand Cayman later this year in which two genetically engineered strains (the second strain apparently being one in which the male mosquito also dies) will mate with the normal mosquito population. The concerns will be the effects of random mutation and crossing over between sections of DNA in this three way mix.

The reason that they can breed repeatedly in the laboratory production plant but can only and mate once after release is that prior to release they are exposed to an antibiotic that prevents the autodestruct mechanism kicking in. A somewhat similar idea was used in the fictional book and movie Jurassic Park, where dinosaurs were genetically engineered so that they required the amino acid lysine. This was supposed to prevent the cloned dinosaurs from surviving outside the enclosed area by forcing them to be dependent on lysine supplements provided by the park's staff. As their hired Chaos theorist Dr. Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum) noted, nature nonetheless found a way.

That anything can foul up is most unlikely to occur on Cayman, but how much “most unlikely” is, is what is currently raising concern in the US. Mutation and crossing over is basically random, and the consequences for the new DNA that arises are extremely poorly understood.